South Sudan has accepted eight deported migrants from the United States, most of whom are not its citizens, but the East African country is signaling it wants something in return. As the Trump administration pushes its aggressive immigration crackdown, South Sudan is seizing the moment to request political favors, including the lifting of U.S. sanctions on top officials, reinstatement of revoked visas, renewed access to U.S. financial systems, and support for its internal political agenda

At the center of these requests is Benjamin Bol Mel, South Sudan’s de facto number two and a likely successor to President Salva Kiir, who remains under U.S. sanctions for alleged corruption. In diplomatic exchanges seen by POLITICO, South Sudan formally asked Washington to remove sanctions on Mel and reconsider a blanket visa revocation policy imposed in April. The country is also asking the U.S. to support the prosecution of its former first vice president, Riek Machar, currently under house arrest.

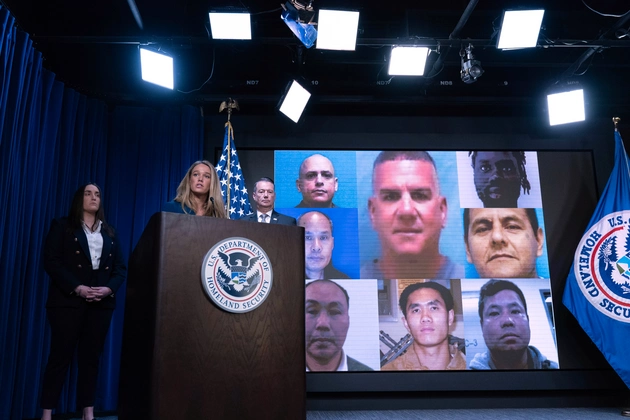

The Trump administration hasn’t agreed to any of the requests, and relations remain fragile after years of war, authoritarian backsliding, and human rights abuses. Still, Juba has been cooperative in recent deportations, receiving eight migrants this month from countries including Cuba, Laos, Mexico, Myanmar, and Vietnam. Only one of them is South Sudanese. They are being housed in a secure facility while South Sudan works on repatriating them to their countries of origin.

Though no formal deal has been struck, high-level talks are ongoing. South Sudanese officials, including their foreign minister, recently met with senior White House and State Department advisers. The administration has similarly approached other African nations like Eswatini and Rwanda, seeing the continent as a region open to negotiation, where diplomatic leverage and foreign aid can shape outcomes.

These efforts reflect a broader strategy: find third-party nations willing to accept deportees who can’t be returned to their home countries. For African governments, it’s a chance to extract political or financial gains. The U.S. has already signed agreements with Eswatini and El Salvador and has floated similar deals with at least 15 African nations.

Immigration experts warn this approach is legally and ethically fraught. Human rights groups are concerned that deportees, including those with criminal records, are being sent to unstable or repressive countries with little transparency or oversight. South Sudan, in particular, remains under a U.S. travel warning and is heavily reliant on American humanitarian aid. Yet the State Department is standing firm on issues like the treatment of political rivals and has reiterated calls for South Sudan to end Machar’s house arrest.

A recent Supreme Court ruling gave the Trump administration more freedom to deport people to third countries, helping fast-track the South Sudan transfers. Observers say the administration is using a small number of highly publicized deportations to send a loud message on border control. For South Sudan, cooperation could mean improving its international standing — if the U.S. is willing to listen.