Mexican authorities are dismantling much of a large migrant tent city built along the Rio Grande in Ciudad Juarez after the wave of mass deportations from the United States that officials once feared has not occurred at the projected scale.

The temporary shelter was erected in late January 2025 under the federal government’s “Mexico te Abraza” (Mexico Embraces You) initiative. The program was launched in anticipation of aggressive immigration enforcement measures promised by U.S. President Donald Trump following his return to office on January 20, 2025. Similar temporary facilities were established in eight other Mexican border cities as part of a coordinated preparedness strategy.

In Juarez, just across from El Paso, Texas, the government installed a dozen large white canvas tents designed to collectively accommodate up to 2,500 deported migrants per day. The complex included a fully operational kitchen, dining areas, portable toilets, showers, and basic administrative spaces intended to process and assist returnees. The site was positioned near the international border to facilitate rapid reception of individuals removed by U.S. immigration authorities.

After 12 months of operation, however, the numbers have fallen far short of those early projections. Instead of receiving thousands daily, the Juarez shelter has averaged approximately 1,700 individuals per month. Most migrants stay no longer than one or two days before traveling onward to their hometowns or other destinations within Mexico.

As a result of the lower-than-expected flow, authorities have dismantled most of the tents. Only four structures remain standing, and just one appears to be actively housing deportees. The remaining tents are reportedly being used by the Mexican military. Media access to the facility has been limited, and attempts by reporters to interview deportees have been restricted by security personnel.

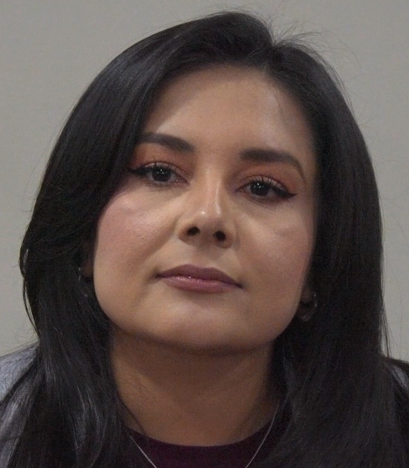

Mayra Chavez, regional director of Mexico’s Bienestar (Welfare) program in the state of Chihuahua, said the camp’s operations are being adjusted in response to actual demand. In February, the shelter has received an average of about 50 individuals per day, though daily totals fluctuate. Since opening, the Juarez site has processed and assisted 20,453 people, she said.

Chavez noted that not all deportees arriving from the United States through El Paso are routed to the tent facility. Mexico’s National Migration Institute (INM) sometimes transfers returnees crossing international bridges to the permanent Leona Vicario shelter in central Juarez. Additionally, Mexican nationals are not required to remain at the temporary camp and may immediately leave to rejoin family members or travel elsewhere in the country.

U.S. enforcement data also reflects deportation activity that, while substantial, has not overwhelmed Mexican border infrastructure. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security reported on December 10 that 605,000 foreign nationals had been deported since President Trump took office in January 2025. DHS has also stated that approximately 1.9 million immigrants have self-deported during the same period. Meanwhile, the Mexican government has recorded the expulsion of 146,000 of its citizens from the United States in 2025.

Despite these figures, border cities such as Juarez have not experienced sustained daily surges requiring the full use of large temporary encampments. In Nogales, Sonora, officials recently announced they would clear out a similar shelter constructed at a sports complex due to low occupancy rates.

Through the Bienestar program, the Mexican government provides a package of support services to returning citizens. These include enrollment in the national public healthcare system, discounted transportation to their communities of origin, and a 2,000-peso debit card — roughly $116 — to assist with immediate expenses. Officials say the assistance is intended to facilitate rapid reintegration and reduce the risk of re-migration.

Chavez added that many deported individuals express concern about property, savings, wages, or other assets left behind in the United States. Financial matters and unresolved obligations are among the most pressing issues facing returnees. In response, the Welfare Office has established a department dedicated to helping Mexican nationals recover money or address pending financial claims.

While the anticipated mass deportations have not occurred at the scale initially feared, Mexican authorities say they remain prepared to expand or reconfigure shelter operations if enforcement patterns shift. For now, the downsizing of the Juarez tent city reflects a recalibration of resources in line with current migration flows along the U.S.-Mexico border.